Department of Pathology, National Institute of Traumatology, Budapest, Hungary

Photos and/or copies of one hundred Upper Paleolithic (45,000-40,000 to 10,000 BP) statues were studied, the photos having been taken from the frontal, lateral and back view. Among the 97 female idols studied, 24 were skinny (mainly young women), 15 were of normal weight, while more than half of them (51) represented overweight or very obese females whose breasts were also extremely large. The figurine analysis revealed various types of obesity. Increased fat tissue deposition can be seen in the following body parts: belly only in 2 Venus figurines, belly + hip in 10, belly + gluteal + hip in 14, belly + hip + gluteal + femora in 24 and diffuse obesity in one. Steatopygia (derived from the Greek “steato” meaning fat, and “pygia” meaning buttocks and describing excessive fat of the buttocks) was observable in 7 idols, although these females were not particularly overweight and had a reasonably thin waist and legs. Only seven statues were in the state of advanced gravidity (pregnancy). The presence of such a small number of gravidity statuettes challenges the general view concerning Venus idols, namely, that they all represent female fertility.

Obesity, Paleolithic era, Sculptures, Steatopygia

INTRODUCTION

In 1926 K. Lambrecht1 stated “Only the bones of our ancestors remain until today, the soft-tissues having decomposed. How much more we would surely know about our ancestors’ physiology if only the remains of one frozen human mummy were discovered in the Siberian ice-sheet, just as have been the dozens of mammoths and woolly rhinoceros” The truth is that skin color, hair, body habitus, body mass and surface area as well as the various types of obesity and steatopygia cannot be recognized based on bones alone. Nevertheless, examination of Upper Paleolithic sculptures may help us identify the physiologic habitus, the body weight and the body proportions of women of the Upper Paleolithic Era.2-4

With regard to these prehistoric artworks, one may draw a distinction between paintings on the walls of caves, rock shelters and open-air sites (parietal or cave art) and movable works (portable art). Portable art is further classified according to its material (organic or inorganic) and its durability (impermanent or long-lasting). Portable art includes sculpted figures and innumerable sets of decorated stone plates.5 Their topics varied from groups of animal figures and human forms to abstract, none of them, however, depicting landscapes. There were very few human images, these representing female, male and indeterminable, and mixed forms, including some that combine human and animal traits, the most common being depictions of females. The statuettes are almost invariably nude and the sex can be identified by their facial features or their vertical body shape. Among the extremely interesting statues, male figurines are scarce as opposed to female figurines. One of the most distinctive innovations of the Upper Paleolithic is the emergence of symbolic, imaginary artistic representations, this signifying the need to pass on aesthetic and notional concepts.

A considerable number of so-called Venus idols have been found throughout most of Eurasia, from Spain to the Amur River,6,7 male figurines being isolated and sporadic in their spatial distribution. Thus, more than 97 percent of these statuettes have female characteristics, whereas male images are mainly restricted to cave wall paintings.8 Examining the idols, we were able to identify their body habitus,2,9-11 the social background of the prehistoric period always needing to be taken into consideration in any attempt to evaluate the characteristics of ancient female obesity.12-15

MATERIAL

Photos and/or copies of one hundred (3 male and 97 female) Upper Paleolithic statuettes were studied. The photos were taken from the frontal, lateral and back view. The female idols were excavated from Western Europe in regions across the European Plain and as far as Lake Baikal and the Amur River. They comprise 12 from France, 60 from Russia, 3 from Ukraine, 6 from the Czech Republic, 7 from Italy, 4 from Austria, 3 from Germany and 1 piece each from Switzerland and Turkey. Most of the idols were engraved on mammoth ivory or mammoth bone (metacarpals), as well as limestone, serpentine, amphibolyt, hematite and in rare cases burnt clay. The majority of the Venuses were nude, only the Siberian specimens showing clothing and hoods. The chronological age and stature of the sculptures are known from previous studies in which the body weight was calculated based on the estimated thickness of abdominal fatty tissue as described by Kosa and Zollei16 in 1975.

RESULTS

Among the 97 female idols studied, 24 were skinny (mainly young ladies) and 15 of “normal” weight. All of these statues had small breasts, with the exception of two. More than half of the statuettes (51) represented overweight or very obese females; in most cases, their breasts were also extremely large (Figures 1 and 2).

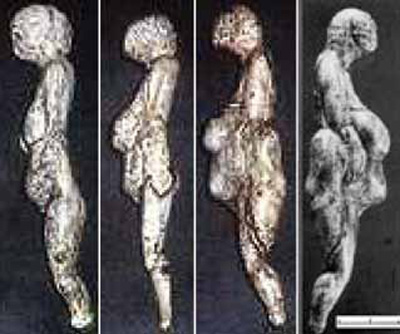

Figure 1. Avdeevo (Russia). Mammoth ivory, 12-15 cm. tall. 20,000 BP. The Avdeevo figurines demonstrate the transition from the normal weight to the overweight and extremely obese female.

Steatopygia (derived from the Greek “steato” meaning fat and “pygia” meaning buttocks and describing excessive fat of the buttocks), was evident in 7 idols although these females were not particularly overweight and had a reasonably thin waist and legs. The condition is characterized by distension and extreme fatness in the buttock area alone. This deformation, which is observable today mainly among women, is also called Hottentot Bustle because it was — and occasionally still is amongst women of certain African tribes — common in Hottentot people. Today it has been ascertained that steatopygia was widespread throughout Eurasia during prehistoric times, not only in regions with a hot climate but also in the colder northern territories17 (e.g. present-day Russia).

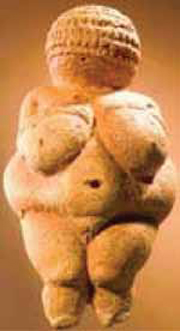

Figure 2. Venus of Willendorf (Austria). Limestone, 23,000-21,000 BP. The idol is 65 mm tall, while the circumference of the belly is 102 mm.

The Avdeevo Venuses demonstrate the transition from normal weight to the overweight and excessively obese female (Figure 1). The figurine analysis showed the various types of obesity. Fat tissue deposition can be seen in the following body parts: belly only on 2 figurines; belly + hip on 10; belly + gluteal + hip on 14 idols, belly + hip + gluteal + femora on 24 and diffuse obesity in one Venus (Figures 3). More than two thirds of the obese statues had giant breasts hanging down to the crista iliac or to the suprapubic region. A hypertrophic (enlarged) breast was visible in 39 idols.

The estimated body weight of the obese figurines would have ranged between 85 and 105 kg if the models were 155 cm tall, whereas, the body weight of skinny and normal weight figurines ranged from 43 to 54 kg.

Figure 3. Catalhoyuk, (Turkey). Limestone, 5.8 cm 22,000-20,000 BP. Diffuse fatness is visible on the idol.

Seven statues are in the state of advanced pregnancy. The presence of only a small number of gravidity statuettes calls into question the generally accepted interpretation of Venus idols, namely, that they all depict female fertility. The Venus figurines display numerous pathological conditions such as genu valgum in 3 cases and genu varum in 2 cases. The genu varum and curvature of the lower limbs shows signs of a healed rachitis. Hyperlordosis of the lumbal spine was noted in 10 figures and in the cervical spine in 6, while kyphosis of the dorsal spine was observed in 3 idols. Hernia of the navel (umbilical hernia) was identified in one figurine. Hypertrophic (enlarged) breasts were visible in 39 idols.

DISCUSSION

The classifications of Abramova,18 Bereczki6 and Jozsa15 include three types of idols:

Classic type with proportionate body. In the present classification, normal body weight females. The estimated weight of these figurines varied between 43 and 54 kg.

Skinny type with thin body parts and limbs. In the present categorization, skinny females. Their estimated body weight varied from 38 to 45 kg.

Venus type with over-stressed body parts. In the present classification, obese females (more than 10 kg compared with the ideal body weight), and excessively obese females (more than 20 kg compared with the ideal body weight).

The body height of Neanderthal females ranged from 152 to 156 cm and the “normal” body weight varied from 50 to 55 kg.10 In the Upper Paleolithic (earlier than 12,000 BP) the females were small and robust2 with a mean height of 158 cm and an estimated average body weight of 54 kg The association of fat with fertility has been widely discussed in the anthropological literature.19,20

Throughout the Paleolithic Era there were frequent periods of famine when obesity would have been rare21,22 as opposed to the era of the sculptures where skinny subjects are rare and obesity is frequently seen.22 How can we resolve this contradiction? I would advance the hypothesis that obesity during this remote age expressed ideal beauty, being considered aesthetically most desirable, though it cannot be excluded that in some societies overweight females were common. This, in my assessment, could explain the large proportion of obese females portrayed amongst the figurines of the Paleolithic Era.

REFERENCES

1. Lambrecht K, 1926 Az osember (The early man) Dante, Budapest.

2. Hermanusen M, 2003 Stature of early Europeans. Hormones (Athens) 2: 175-178.

3. Hudson MJ, Aoyama M, 2007 Waist to hip ratios of Jomon figurines. Antiquity 81: 961- 970.

4. Hufschmidt HJ, 1977 Body proportion in sculpture and painting. An anthropological and historical essay. Arch Psichiatr Nervenkr 224: 187-202.

5. Fiedorczuk J, Bruthard B, Kalstrup E, Schild R, 2007 Late Magdalenien femine flint plaquettes from Poland. Antiquity 81: 97-105.

6. Bereczki A, 2000 Beitrage zur Typologisierung der Venusstatuetten der Kultur Gravettien. Praehistoria (Miskolc) 1: 173-183.

7. Poikalainen V, 2001. Paleolithic art from the Danube to Lake Baikal. Folklore (Tallin). 18/19, 1-26.

8. Angulo-Cuesta J, Garcia-Diaz M, 2006 Diversity and meaning of masculine phallic paleolithic images in Western Europe. (Article in Spanish with English summary). Acta Urol Esp 30: 254-267.

9. Harding J R, 1976 Certain Upper Paleolithic “Venus” statuettes considered in relation to the pathological condition known as massive hypertrophy of the breasts. Man 11: 271-272.

10. Helmuth H, 1998 Body height, body mass and surface area of the Neanderthals. Z Morphol Anthropol 82: 1-12.

11. Helvin H, 1973 Pathological findings of early and pre-historic sculptures. Gegenbaurs Morphol Jahrb 119: 434-445

12. Colman MDE, 1998 Obesity in Paleolithic era? The Venus of Willendorf Endocr Pract 4: 58-59.

13. Duhard J-P, 1988 Peut-on parler d’obesite chez les femmes figurees dans les oeuvres parietales et mobilieres paleolithiques? Prehistoire Ariegeoise 43: 85-103.

14. Jozsa LG, 2008 Az elhizas es abrazolasa az oskokorban. (Obesity in the paleolithic era, as portrayed on sculptures) (Article in Hungarian, with English resume). Orvosi Hetilap (Medical Weekly) 149: 2307-2312.

15. Jozsa LG, 2010 What was the stature of the paleolithic women? Folia Anthropol 9: 19-37.

16. Kosa F, Zollei M, 1975 A hasfali zsirparna vastagsaganak osszefuggese a testhosszal es a testsullyal. (Article in Hungarian) (Connection between the thickness of lipid layer of the belly, and the body weight and body stature). Rendororvosi Tudomanyos Ulesek kozlemenyei 6: 209-213

17. Gvozdover MD, 1989 The typology of female figurines of the Kostenski Paleolithic culture, (Article in Russian, with English resume). Soviet Anthropol Archeol 27: 32-94.

18. Abramova ZA, 2000 Les Venus du Paleolithique superieur de la Siberie: des questions typologiques, comparatives et chronologiques. Praehistoria (Miskolc) 1: 161-171.

19. Goldman B, 1960 - 63. Typology of the mother-goddess figurines. Jahrbuch fur Prahistorische und Ethnographische Kunst 20: 8-15.

20. Rice PC, 1981 Prehistoric Venuses: Symbols of motherhood or womanhood? J Anthropol Res 37: 402-414.

21. Cheng TO, 2005 Obesity, Hippocrates and Venus of Willendorf. Int J Cardiol 9: 2-16.

22. Pontius AA, 1986. Stone age art “Venuses” as heuristic clues for types of obesity: Contribution to icondiagnosis. Percept Mot Skills 63: 544-546.

Address for correspondence:

Laszlo G. Jozsa, Professor Emeritus of Pathology,

3648 Csernely, Tancsics u. 9./Hungary, e-mail: jozsalg@gmail.hu

Received 14-05-11, Revised 15-06-11, Accepted 25-06-11